Reflecting the uncertainty surrounding the incoming administrations effect on the economy, this NYT article offers a contrary view to the on-going escalating interest rate environment.

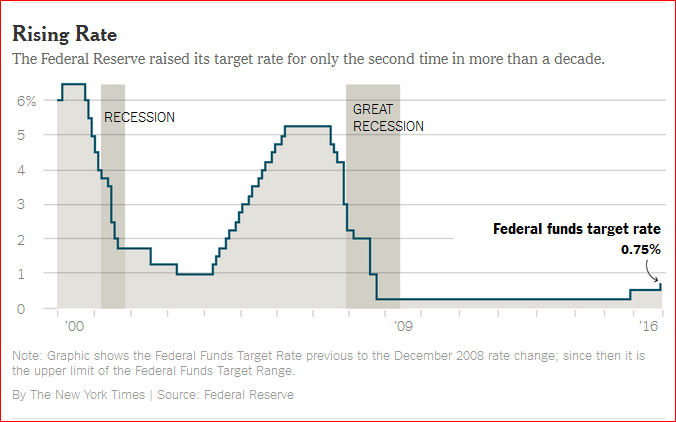

Higher interest rates are on the way. That, anyway, is the prediction increasingly baked into financial markets. Donald J. Trump’s policy agenda — big tax cuts and new infrastructure spending — seems to point in that direction. And the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point on Wednesday, with plans for more increases next year.

But what if that’s wrong?

There’s no doubt that the stated goals of President-elect Trump imply that rates will be higher in a couple of years than they are today. As my colleague Binyamin Appelbaum writes, any stimulative fiscal policy from the Trump administration could well face an equal and opposite tightening of monetary policy by a Fed that raises interest rates.

The central bank will seek to prevent too much inflation from breaking out in an economy it believes is getting close to operating at its full potential, which means Mr. Trump’s stimulus might run up against the Fed chair Janet Yellen’s (and perhaps her successor’s) counter-stimulus.

But it’s worth looking at the two big ways that these forecasts could be wrong, and worth considering that the era of low rates might stick around a bit longer than some of the postelection discussion might have suggested. First, the Trump agenda might pack less of a growth punch than some have imagined. If so, you would expect the same cautious approach to rate increases from the Fed.

Second, even if the economy does start growing faster, future Trump administration appointees could change their tune on the desirability of higher interest rates. That has been the pattern with other populist politicians of the Trump mold around the world. Politicians, once in office, tend to learn that they like low interest rates. It’s easy to envision a Trump administration pushing for cheaper money and the Fed attempting to hold the line to prevent inflation.

If Trump-Era Growth Is Less Than Advertised

On the first point, it’s worth diving into the details of the Trump policies that led to the postelection-day market rally in stocks and the sell-off in bonds.

He wants to enact major tax cuts, for one, which all else being equal, would tend to create a short-term boost in economic growth and higher interest rates. But there are some early signals that the Republican lawmakers who actually have to pass any changes to tax law, especially those in the Senate, are wary of tax cuts that would increase the budget deficit as much as Mr. Trump’s campaign plan would.

“My preference on tax reform is that it be revenue neutral,” the Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell told reporters this week.

Another big plank underneath the idea that Mr. Trump’s economic policy will be stimulative is an expectation that he will embrace a large-scale infrastructure spending package.

But while the president-elect mentioned that idea in his election victory speech, he hasn’t put much meat on the bones of the plan since. The details matter a great deal for how much an infrastructure plan could lift growth. For example, tax credits that make the finances of building toll roads more favorable are less likely to create a huge boost in activity than spending on upgrading physical infrastructure outright.

So on both tax cuts and infrastructure, there’s no guarantee that the actual scale of stimulus will match some of the early postelection talk. Economists at JPMorgan Chase, for example, are forecasting economic growth of just under 2 percent for both 2017 and 2018 — about the same as the pace of the last six years.

And that’s before you factor in the risk that some elements of Trump economic policy could end up being a drag on growth. Think of a trade war with China or Mexico, immigration restrictions that limit the supply of labor or geopolitical disputes.

All that gives the Fed every reason to take a wait-and-see approach to shaping its policy. If the Trump economy really starts to take off, the Fed could move more aggressively to raise rates. But it will do that based on actual evidence and data rather than the president-elect’s rhetoric.

If Trump’s Fed Governors Choose to Keep Rates Low

Which leads to the other scenario, in which the economy accelerates at the risk of overheating. History is littered with examples of politicians in that circumstance pressuring their central banks to keep rates low to encourage growth.

In 1972, that was Richard Nixon, pressuring the Fed chairman Arthur Burns to keep money flowing freely in the economy to help his re-election chances. In modern times, populist right-wing politicians in Hungary and Turkey have undermined their central banks’ independence, pushing for lower interest rates.

There are two vacancies on the Fed’s seven-member board of governors already, and Ms. Yellen’s term as chairwoman expires in February 2018; the vice-chairman Stanley Fischer’s term is up in June of that year. Add it up, and within 18 months of taking office, Mr. Trump could have appointed a majority of the Fed’s board, including its chair and vice chair.

That doesn’t mean that Trump nominees for those jobs would necessarily refrain from rate hikes if they believed they were warranted. Many potential Republican Fed nominees have opposed the low interest rate tendency of the Fed under Ms. Yellen and her predecessor, Ben Bernanke.

For the past few administrations, the accepted practice has been that presidents should refrain from weighing in on monetary policy and let the Fed act independently. But Mr. Trump has described himself as a “low interest rate person” and was willing to scrap that precedent by attacking Ms. Yellen by name during the campaign.

Also, to be technical about it, even if the Fed kept its short-term interest rate targets low despite rising inflation, long-term interest rates, which are determined by the bond market, would probably rise.

If there’s one thing we know about Mr. Trump, it’s that he doesn’t feel bound by the traditions that have governed how recent presidents have acted. And that means that the future of United States interest rate policy, like so much else, is up for grabs.